(Editor’s Note: Photos by Merissa Quek.)

The cover of the Gwangjin-gu (Slogan: A City of elegance, livable Gwangjin) promotional booklet that the kind docent at the Achasan Goguryeo History Musuem handed to me shows an aerial shot of the district, mostly a confetti smattering of densely packed apartment rooftops, broken by the occasional vertical tower. At the eastern edge of this evenly dappled expanse, however, and seeming to rise almost straight out of the Han, is the massive green bulge of Acha Mountain (아차산), dwarfing everything around it.

Unlike Bukhansan or Inwangsan, I knew very little about Achasan, which was probably due in large part to the fact that we just haven’t been to Gwangjin-gu that often for this project, despite the district’s elegance. It turns out, though, that the mountain is rich with both stories and history.

Upon arrival, I headed straight for the mountain, leaving from Exit 2, passing an old woman selling homemade potato and sweet potato chips on the sidewalk, and turning left on Jayang-ro (자양로), following the signs on the corner. Immediately I could see the camo-pattern brown, green, and tan of the mountain up ahead. Jayang-ro cut through a lower-middle class neighborhood of mid-rise apartments, restaurants, and grocers, many of the latter having taped up store flyers on every available power line post.

When the road ended I turned right onto Yeonghwasa-ro (영화사로), and immediately found myself going uphill. Up on the left was a small Buddhist temple called Hwayang Temple (화양사), fairly nondescript save for the large stone Buddha statue in back. Just a few dozen meters past the temple I came to a set of wooden stairs, the entrance to Achasan’s Goguryeo Pavilion Trail (고구려정길).

Rubber-matted with rope handrails, the stairs ascended alongside large coils of barbed wire that separated the trail from, ironically I guess, another Buddhist temple. Shortly the stairs gave way to a stone path surrounded on either side by kinky pines, and after walking up the trail for a bit I paused to turn around and look back behind me – the gently twisting trees rising up out of the smoothly sloping earth brought to mind hair follicles emerging from a scalp, giving me the sensation that I was walking across a giant’s head.

Achasan, like every other mountain in Seoul, was home to numerous magpies, but I also spotted a woodpecker, a spotted dove, and a Eurasian jay. As I went up the mountainside there were no signs that I was still in Seoul – no visible buildings, no sounds of traffic – until, that is, the path rather suddenly and rudely came out right next to a giant white tower carrying power lines across the mountain.

A short ways past the tower the trail emerged from the trees and opened onto a large rocky outcropping, at the top of which was the Goguryeo Pavilion. Several hikers were resting on the outcropping, taking in the scene below them, but if you slip off your shoes and climb up the pavilion the views are even more stunning. And thanks to its unique position, the views from Achasan are notable for two reasons. Located at the eastern edge of the city, it’s one of the most popular spots in the capital for viewing the first sunrise of the New Year, the slightly masochistic ritual that Koreans love so much, and every January 1st a festival is held here. It’s also the closest natural vantage point in Seoul for viewing the Han from above, and from the pavilion you can watch as it enters Seoul, runs south, and then, glittering, curves northwest at the bend between Jamsil and Ttukseom. From here too you can see practically half the city. Due south, Olympic Bridge crosses the water and the monstrous new Lotteworld 2 tower rises up behind it. Southwest are the skyscrapers of Gangnam, and further west, past all the little Lego block apartments, landmarks like Doota Tower, Seoul Tower, and the 63 Building rise above the city’s fray, while beyond those in nearly every direction are the undulating mountains that surround the city. And, should you tire of the view, there’s a small bookshelf in the pavilion where you could pick something up to read.

From the pavilion I watched as a flock of pigeons circled in the air, circled again, touched down on the rocky outcropping, and then immediately changed their collective minds, rising up together in a rustle and heading further down the mountain. I followed their lead and left the pavilion, but instead of heading back down I continued up the slope to a fork in the path where a sign on the right pointed to the Achasan Fortress Wall (아차산성).

From the pavilion I watched as a flock of pigeons circled in the air, circled again, touched down on the rocky outcropping, and then immediately changed their collective minds, rising up together in a rustle and heading further down the mountain. I followed their lead and left the pavilion, but instead of heading back down I continued up the slope to a fork in the path where a sign on the right pointed to the Achasan Fortress Wall (아차산성).

Owing to its strategic location overlooking the Han and the surrounding valleys, Achasan was for centuries a site of military importance and territorial battles, particularly during the Three Kingdoms period, when Goguryeo, Baekje, and Shilla vied for control of the area. According to the aforementioned promotional booklet, the mountain and the surrounding area is the largest Goguryeo historical site in the country. Though the bulk of the Goguryeo kingdom existed in what is now North Korean and northeastern China, its temporary occupation of the area around Seoul left behind numerous relics – including roof tiles, jars, metal helmets, and farming implements – over 6,000 of which have been excavated here, as well as several architectural relics, of which the fortress wall is one of the most significant.

Walking up towards the old wall I paused to read one of the plaques explaining a bit more about it, and as I did so I was interrupted by a loud noise coming from somewhere on my right. Looking down the path I spotted an ajumma who was tilting her head back and yelling ‘Aaaaaaaahhhhh!!!!!’ at the top of her lungs. She repeated this several times before apparently deciding she’d gotten it out of her system and sauntering down the path.

The fortress wall, Historic Site No. 234, is believed to have been constructed by the Baekje dynasty, some time prior to 286 CE, before being taken by Goguryeo at the end of the 4th century. Seven meters tall and over a kilometer in circumference, it surrounded Achasan’s peak and contained within it buildings, a well, and a pond. What remains of the fortress today is thought to have been made during the post-7th century period of Shilla control.

What remains is, admittedly, rather minimal, and I spent much of my time looking at a wall behind a white fence wondering if what I was looking at was the wall or just a wall, constructed later to guard against rockslides or something. After walking back and forth a while I felt reasonably satisfied that it was the wall, an uncertainty that I suppose says two things about it. One, it’s not exactly eye-catching, just some gray rectangular stones with moss clinging to them; two, it was some pretty good craftsmanship if it made me wonder whether something built over a millennium ago was maybe just a few decades old. For the curious, signs along the trail also post pictures and information of artifacts recovered from here.

Back at the fork in the trail above Goguryeo Pavilion, going left will take you up towards Achasan’s peak and, if you were to continue further, that of Yongmasan. Climbing further up I passed some ajummas and ajeosshis with radios playing old pop tunes strapped to their bags and a guy coming down the hill carrying his fat little dog, who’d apparently had it. Soon after that I came to another viewing platform with sweeping views of the Han, eastern Seoul, and Guri. Several dozen meters further up was Achasan Fort No. 1 (아차산1보루), where the views were even better.

Signaling the area’s former military import, the connected Achasan, Yongmasan, and Mangwusan range held around 20 Goguryeo forts, the remains of 17 of which still exist. Believed to have been built mostly in the late 5th century, they didn’t hold out very long, as combined Shilla and Baekje forces overran the Han River basin in 551. Collectively designated Historic Site No. 455, the forts were built at half-kilometer intervals, and some held forges or grain processing mills. They’ve also provided rich archaeological finds.

Achasan Fort No. 1 is located on a little windswept promontory, and although its top is fenced off you can still clearly understand why Goguryeo generals might have chosen the location, as even from the promontory’s base you’re afforded a commanding 270-degree view encompassing everything to the east, south, and west.

Back down near the entrance to the Goguryeo Pavilion Trail that I initially came up, a wooden boardwalk splits off from the trail, leading east to the Achasan Ecology Park (아차산생태공원). Arranged around the base of the mountain, it’s a large area with facilities including a performance stage, badminton courts, picnic tables, and even some funhouse mirrors that will stretch and smoosh and flip you. Though it can be accessed straight from the mountain, the park’s main entrance is most directly accessed by passing the trail entrance and continuing on Yeonghwasa-ro. Next to a parking lot is a large manmade pond and several walking paths that wend through the park. Here you’ll also find the small Achasan Goguryeo History Museum (아차산고구려역사문화 홍보관), which offers information on the area’s history, presents scale models of the remains of two forts, exhibits pieces of excavated pottery, and displays Goguryeo costumes. Information is entirely in Korean, but the nice lady working will likely provide you with the same bilingual Gwangjin-gu booklet that she did me.

Back down near the entrance to the Goguryeo Pavilion Trail that I initially came up, a wooden boardwalk splits off from the trail, leading east to the Achasan Ecology Park (아차산생태공원). Arranged around the base of the mountain, it’s a large area with facilities including a performance stage, badminton courts, picnic tables, and even some funhouse mirrors that will stretch and smoosh and flip you. Though it can be accessed straight from the mountain, the park’s main entrance is most directly accessed by passing the trail entrance and continuing on Yeonghwasa-ro. Next to a parking lot is a large manmade pond and several walking paths that wend through the park. Here you’ll also find the small Achasan Goguryeo History Museum (아차산고구려역사문화 홍보관), which offers information on the area’s history, presents scale models of the remains of two forts, exhibits pieces of excavated pottery, and displays Goguryeo costumes. Information is entirely in Korean, but the nice lady working will likely provide you with the same bilingual Gwangjin-gu booklet that she did me.

Directly opposite the park’s main entrance and half-hidden among the trees is a small staircase that leads up to a path that leads up to the Hongnyeonbong Forts (홍련봉보루), which are believed to have been the nerve center for the entire chain of Goguryeo defenses on Achasan. After a steep climb up, the first fort I came to was Hongnyeonbong Fort No. 2. Excavated in 2005 and again in 2012-2013, it’s thought to have been the logistics base for the Achasan system, and pottery kilns and other production facilities were discovered here. 150 meters to the south, it’s presumed that Fort No. 1 served as the headquarters for the local military, as a particular type of building located only in royal palaces or important government buildings was discovered there. Although unlike at Achasan Fort No. 1 I could walk right up to the edge of the sites here, there was unfortunately nothing to see, as both sites were covered by enormous blue tarps weighed down by fluorescent orange sand bags, giving them the appearance of a giant blueberry Jello mold. Off near the far end of Fort No. 2, which is much bigger and longer than No. 1, approximately the length of a football pitch, I could see some men on top of the tarp, working on securing ropes or prepping a dig; it was hard to tell. Though there might not be anything to see at present, fortunately there are plans for restoration of Fort No. 2, to be completed and opened to the public sometime this year.

Leaving the forts and walking back towards the station I came to Yeonghwa Temple (영화사), just on the northwestern side of the ecology park. An imposing wooden gate supported by two enormous pillars marked the entrance, but the epic feeling was diminished by the squeals of seven and eight-year old kids getting out of class at the elementary school next door. The temple’s main courtyard was marked by a large bell pavilion that held an imposing metal bell, and by a 19.5-meter tall zelkova tree believed to be around 370 years old. The zelkova seemed caught between seasons, its leaves near its trunk still a vibrant green but those near the tips of branches having turned crimson and gold. Yeonghwa Temple itself has an even older, more venerable history than the tree in its courtyard, having been founded by Euisang Daesa (의상대사) in 672 before being moved to its present location in 1907.

Besides the Achasan area, Achasan Station provides quick access to another major attraction, one we’ve visited before: Children’s Grand Park (어린이대공원). While the main entrance is just outside of the station of the same name on Line 7, Exit 4 of Achasan drops you off directly on the long approach to the park’s rear entrance. The plaza just outside the exit seemed, contradictively, to be more a hangout for grandfathers than one for their grandkids. Past the gathered and gabbing seniors, though, the walkway was lined with stalls selling Pororo drinks, dried squid, boiled silkworm larvae, and cotton candy in plastic cups. Speakers attached to lampposts played children’s songs.

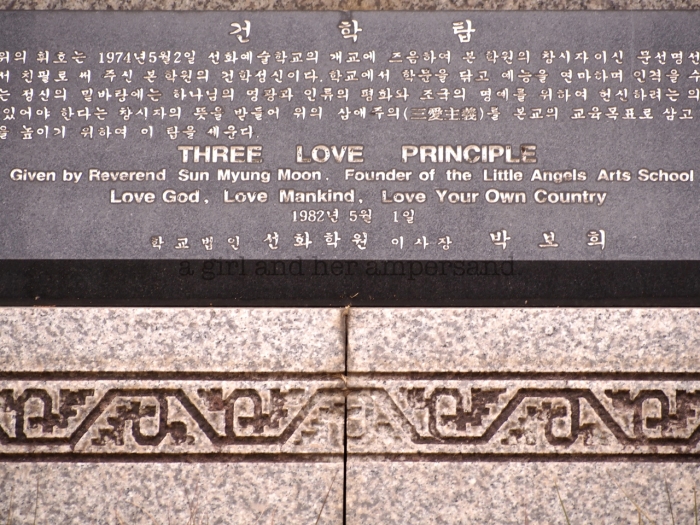

A bit oddly for the entrance to a children’s park, I thought, about halfway down the walkway was flanked by a pair of military statues. On the left, high atop a pedestal, the great Goguryeo general Eulji Mundeok (he of Eulji-ro (을지로) downtown) lunged forward with his sword to run through any enemy that might be in front of him. On the right (and much more relaxed) was John B. Coulter, a former Lieutenant General in the U.S. Army. Born in San Antonio, Texas, he led the army’s IX Corps to victory in the battle of Pohang in 1950 before serving as the Deputy Commanding General of the Eighth U.S. Army. Post-Korean War he performed as the Agent General of the United Nations Reconstruction Agency. After the statues a trio of large white halls housed the park’s Universal Ballet, Universal Art Center, and the Little Angels, a children’s folk ballet founded by Sun Myung Moon, founder of the Unification Church, which I find all sorts of creepy.

A bit oddly for the entrance to a children’s park, I thought, about halfway down the walkway was flanked by a pair of military statues. On the left, high atop a pedestal, the great Goguryeo general Eulji Mundeok (he of Eulji-ro (을지로) downtown) lunged forward with his sword to run through any enemy that might be in front of him. On the right (and much more relaxed) was John B. Coulter, a former Lieutenant General in the U.S. Army. Born in San Antonio, Texas, he led the army’s IX Corps to victory in the battle of Pohang in 1950 before serving as the Deputy Commanding General of the Eighth U.S. Army. Post-Korean War he performed as the Agent General of the United Nations Reconstruction Agency. After the statues a trio of large white halls housed the park’s Universal Ballet, Universal Art Center, and the Little Angels, a children’s folk ballet founded by Sun Myung Moon, founder of the Unification Church, which I find all sorts of creepy.

We covered Children’s Grand Park pretty thoroughly in that post, so I won’t rehash everything here. However, the park is quite large, several square city blocks, and a few of its attractions are more easily gotten to via Achasan Station should you be particularly interested in those. If your kid is a train nut, something a lot of kids seem to be, just inside the park’s rear entrance a couple of old Japanese-manufactured trains sit on display, two coal black engines and a couple boxy sky blue and white passenger cars that ran the route between Suwon and Yeoju in the 1950s and 60s.

We covered Children’s Grand Park pretty thoroughly in that post, so I won’t rehash everything here. However, the park is quite large, several square city blocks, and a few of its attractions are more easily gotten to via Achasan Station should you be particularly interested in those. If your kid is a train nut, something a lot of kids seem to be, just inside the park’s rear entrance a couple of old Japanese-manufactured trains sit on display, two coal black engines and a couple boxy sky blue and white passenger cars that ran the route between Suwon and Yeoju in the 1950s and 60s.

Behind the trains is the Kids Farm (어린이 텃밭) for the budding farmer, and, past the trains, the entrance to the Amusement Park (놀이동산), where a few cars from some old rides were parked on display outside the entrance. The Amusement Park seemed to have gotten a makeover since the last time I visited, with a number of new rides, new paint jobs, and a refurbished roller coaster. The first time we came here it was summer, and this was the liveliest, noisiest section of the park, filled with shrieking, running kids. Now it was mid-November, with temperatures in the low teens, and the park was almost deserted. There were, I’m pretty sure, no more than twenty people there, counting parents and the odd twenty-something couple strolling through. But for those kids who braved the cold, they were rewarded with the type of amusement park you dream of, one where there are no lines and you can run from ride to ride never having to wait. About half of the rides in the park had exactly one kid on them – the other half had none – and operators were basically letting the kids go around as long as they wanted. Two particularly hardy siblings had even climbed aboard the flume ride, bundled up in their winter coats, hoods pulled tight against the freezing water that splashed up and over them when their sled barreled down the chute. When they got back to the start the ride operator sent them back around again.

There’s a lot more within Children’s Grand Park – a zoo, botanical gardens, performance theaters, broad green lawns – and it’s large enough that even if you can’t stand kids you won’t have much trouble finding a corner to relax or have a picnic that’s well out of range of the under-ten set. And for history buffs, the park also contains the former burial site of Empress Sunmyeonghyo (순명효), wife of Emperor Sunjong (순종), the last king of the Joseon dynasty. (Sunmyeong never actually served as empress, dying in 1904, three years before Sunjong assumed the throne, but she was granted the title posthumously.) Though she was disinterred and moved to Sunjong’s burial site in Yureung upon her husband’s death, stone statues from the original tomb stand here in close to their original form.

After leaving the park I turned left on Cheonho-daero, Exit 5 behind me, and after a couple hundred meters I arrived at a stretch of the road that is home to Junggok-dong Furniture Street (중곡동 가구거리), yet another of the furniture streets we’ve run into throughout town. Running for about a kilometer and a half, from near Achasan, past Gunja Station, all the way to the Gunja Bridge over the Jungnang Stream, somewhere in the neighborhood of 80 furniture shops are located here. Business seemed a bit slow when I was there, but should you be in need of a new piece for the home you can find all kinds of stuff there: kids desks, sleek and modern couches, stone beds, pink chaise lounges, and tacky stuffed chairs with roses carved into the cresting rail.

After leaving the park I turned left on Cheonho-daero, Exit 5 behind me, and after a couple hundred meters I arrived at a stretch of the road that is home to Junggok-dong Furniture Street (중곡동 가구거리), yet another of the furniture streets we’ve run into throughout town. Running for about a kilometer and a half, from near Achasan, past Gunja Station, all the way to the Gunja Bridge over the Jungnang Stream, somewhere in the neighborhood of 80 furniture shops are located here. Business seemed a bit slow when I was there, but should you be in need of a new piece for the home you can find all kinds of stuff there: kids desks, sleek and modern couches, stone beds, pink chaise lounges, and tacky stuffed chairs with roses carved into the cresting rail.

Both sides of Cheonho-daero are occupied by furniture stores, but if you go out of Exit 1, you’ll find yourself curving onto Yongmasan-ro (용마산로), a busy little commercial road filled with restaurants and businesses of all types. I walked down it for a bit, weaving in and out of the locals doing their evening shopping, before hanging a right on Yongmasan-ro-6-gil (용마산로6길). A couple blocks down brought me to the rear entrance of Sinseong Alley Market (신성골목 시장), which was exactly that and nothing more: a tiny alleyway, maybe two meters wide, with, at most, a couple dozen stalls packed into it. It was a tiny and lean operation, with seemingly just one of everything: one fruit stand, one rice cake vendor, one donut maker, one fishmonger, one seller of dried peppers, one garlic and spices purveyor, one butcher with a sticker in his window proclaiming he’s an ex-marine. It was, in that way, an idyllic market, exactly as one of the kids back at Children’s Grand Park might find in one of their storybooks.

Acha Mountain (아차산), Achasan Fortress Wall (아차산성), and Achasan Fort No. 1 (아차산1보루)

Exit 2

Straight on Cheonho-daero (천호대로), Left on Jayang-ro (자양로), Right on Yeonghwasa-ro (영화사로)

Achasan Ecology Park (아차산생태공원), Achasan Goguryeo History Museum (아차산고구려역사문화 홍보관), and Hongnyeonbong Forts (홍련봉보루)

Exit 2

Straight on Cheonho-daero (천호대로), Left on Jayang-ro (자양로), Right on Yeonghwasa-ro (영화사로)

Yeonghwa Temple (영화사)

Exit 2

Straight on Cheonho-daero (천호대로), Left on Jayang-ro (자양로), Right on Yeonghwasa-ro (영화사로)

Children’s Grand Park (어린이대공원)

Exit 4

02) 450-9311

Hours | 5:00 – 22:00

Zoo Hours | 10:00 – 17:00

Admission | Free, but tickets must be purchased for amusement park rides

Junggok-dong Furniture Street (중곡동 가구거리)

Exit 5

Straight on Cheonho-daero (천호대로)

Sinseong Alley Market (신성골목 시장)

Exit 1

Straight on Cheonho-daero (천호대로), Right on Yongmasan-ro (용마산로), Right on Yongmasan-ro-6-gil (용마산로6길)

Dear Sir,

I really admire what you have done about the Seoul metro line, and I would like to meet you one day if possible.

My name is Mr. Ha Kyung Choi who already contacted you on your report for Dongguk Dae Station

for the explanation on the memorial stone statue of Lee Han Eung.

I am actively engaging in the fields of civis level diplomacy between Koreans and expats in Korea as the president of Senior Public Diplomacy Group of Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Republic of Korea.

We are now planning to hold free concert 2015 International Folk Music & Dance Concert of which details and invitaion you can find “International Folk Music & Dance Concert” page on Facebook.

Please find it and I hope you can come to the concert and meet me. otherwise contact me to my mobile phone .010-3728-6003 and email address you already know.

Thank you in advance.

Sincerely yours,

Ha Kyung Choi

President, Senior Public Diplomacy Group

Thank you so much for the detailed information here! I have had a number of different friends tell me about this area and it looks like there is a lot to do. I really need to check it out.

Thanks Doria!

Pingback: Achasan Mountain (아차산) :: Korea travel tour site info! – Korea Travel Blog

I have seen the Little Angels Korean Folk Ballet perform at the Little Angels Performing Arts Center that you mentioned. The dancers are from the ages of 7 to 17, extremely talented and cute as can be. Being near the Children’s Grand Park is a great and appropriate location for them. I highly recommend them if you can catch one of their performances. I read in their brochure that they have performed at the UN and in over 70 nations around the world.